|

|||||||||||||||||||

Around the Interface in 80 Clicksby Lisa Battle and Duane Degler Read our additional thoughts on the subject, March 2002 IntroductionThe use of computers internationally has increased dramatically. The rapid expansion of the Internet has given people access to the same applications and content anywhere in the world. With this, user expectations are going up—users do not want to learn another culture and another language to perform work. As the market for computers and the information they deliver evolves, the types of people using them will be more of the “late adopters” rather than the “early adopters.” Donald Norman wrote about the expectations of these users, that software “truly meets their needs” and promotes a “good user experience” (Norman, 1998, pp34-36). Importantly, he also emphasizes the need for “no feeling of puzzlement, no loss of control.” As designers, we can’t necessarily rely on current interface conventions that appear to be “standards.” The tools have to match people’s working needs, and now for many people their lifestyle needs. These user expectations are strikingly similar to the expectations we have seen for software to be usable, with market demand growing steadily over the past 4-5 years. We believe the demand for software that is usable across languages and cultures is the beginning of the next wave of demand from users—and the next great challenge for software designers. Software can and should make an extra effort to provide a good user experience. Designing adaptable, internationalized software is difficult in part because of the lack of guidance within the practical literature of software design. The ordinary software developer, the project manager, and the consumer do not have ready sources of non-academic information on this subject. Those books or web sites that deal with the subject tend to be focused on cultural investigation/analysis (del Galdo & Nielsen, 1996) or on detailed programming/translation guidelines (Cross, 1999; Ebben & Marshall, 1999; Sun Microsystems, 2000; W3C, 1998). How do these guidelines translate into the practical design of applications and web sites? There is a need for more holistic checklists of what to think about when designing for the international user (Ishida, 1997). This is why in this article we have tried to cast a wide net across a range of subject areas. We are user interface designers and performance support specialists. We are not experts in internationalization; however, this subject has come up repeatedly in the course of our work. We have been asking ourselves the question: what do we mean by performance, and is it possible to support it internationally? As a result, we have started building our own checklist of questions and issues we think need to be addressed when designing software for international audiences. Performance-centered design and performance support are not just about helping people use software applications—rather, they aim to help people perform real-world tasks successfully and increase the quality of the outcomes. This increases the importance of providing localized support. It isn’t enough to describe in a particular language how to enter data into the software. We need to think about describing how to perform a job successfully within another cultural context. In addition, many people are increasingly doing knowledge work. For them, it isn’t enough to support a task; we also need to be thinking about supporting knowledge acquisition and use across cultural boundaries. Culturally restrictive software could potentially get in the way of that goal. The more we try and make things context-relevant for one group of users, the harder it is to make things culturally relevant for others. What is it?In their book International User Interfaces, Elisa del Galdo and Jakob Nielsen outline three levels of international user interfaces, and confirm that once you pass level one, there is insufficient expertise and experience (del Galdo and Nielsen, 1996, preface). The levels are:

The terms internationalization and localization tend to become lumped together, and there are several definitions of what they mean. While they are closely related, they can usefully represent two ends of a design spectrum. We define internationalization as creating representations that are equally understandable across different cultures. In some cases, this can be achieved through basic symbols (such as arrows, or icons based on objects in nature) that are easily understood. However, in most cases a symbol has to be learned, and thus the use of international symbols leads to a “one-size-fits-all” standard that takes time to become familiar. Eventually, users can learn to understand and conform with de facto standards. Localization, at least in its ideal, involves adapting the software to the language, culture, and norms of the local culture, so there is no cognitive dissonance or need for the people to translate. In a way, localization is like setting group preferences—a collective some levels above user preferences, which tailor an individual person’s experience by allowing him or her to specify how the computer should interact. There is an implied diversity in localization, because the software should support the diversity of culture. In fact, due to the way localization often has to be implemented practically, this is a false diversity. Translating into a language group is not the same thing as translating into a culture. When companies prepare international versions of their software, a translation into French is considered sufficient for all of France, Belgium, Quebec, Martinique and several countries in north Africa. A translation into German is considered sufficient for Germany, Switzerland, Austria, etc., just as English is suitable for Britain, Ireland, North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and anyplace else a specific language group is not catered for. The reality is that while these places do belong to a language group, the dialects, spelling, vocabulary and culture are often very different, and there are different metaphors and ways of working. Translating the language only is what we call “linguification” rather than localization. There is an expectation that the user will still make the effort to bridge other cultural gaps. The Obvious StuffThere are a number of things that tend to get the most immediate attention – partly because they are very irritating to users and partly because they are easier to identify and fix (although the people doing it might not think so at the time!). The purpose of this article is not to dwell on these things, which are covered in detail in other places, but they deserve a mention. These include:

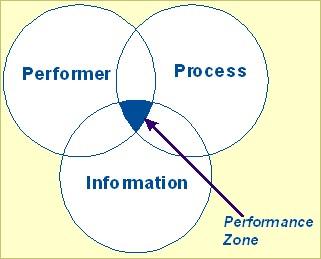

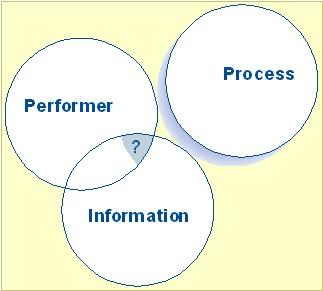

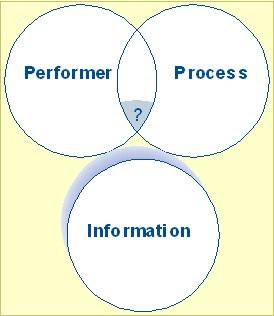

Designing for PerformanceTo support performance for an international audience, we need to examine the key elements of performance in relation to the design of systems. The three-element model of performance design that we use is the one introduced by Gary Dickelman a number of years ago (Dickelman, 1996). The elements are the performer, the process, and the information, which must all be integrated (see Figure 1). Optimal performance, or the “performance zone,” occurs when all three of those elements are working together. If a software product does not take into consideration a whole range of international issues, it can break the link between those elements. We will take each one in turn and look at what happens when it becomes disconnected.

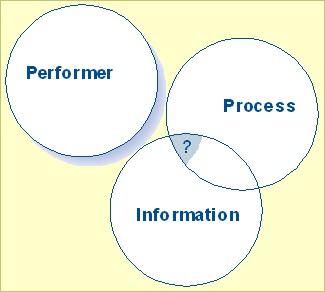

Disconnecting the PerformerWhen we are dealing with internationalization, the primary focus is the performer—not just as an individual, but as a cultural group. The product designed for a performer in one cultural group may not work for people in another. Imagine that we have taken the three-element model of performance and removed the “performer” circle, and then attempted to replace it with a different one (see Figure 2). The new “performer” circle does not fit because the parts are not interchangeable. To reconnect the performer with the process and information, we have to understand the attributes of the cultural group. To plan ahead for supporting a process with an international audience, we analyze it by asking questions like these:

Language

Time

Cultural expectations

Metaphor and representation

The performer’s locale

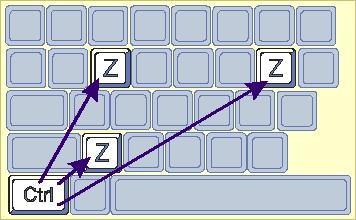

LanguagePerhaps the most obvious difference between groups internationally is the native language. We mentioned earlier that the “linguification” approach to preparing international versions of software involves translating into a major language group, not the local language that people actually speak. We recognize that there may be a practical limit to the number of variations that can be produced, and that people are usually flexible enough to adapt to a different variation of their language. However, when taking this approach, the designer, content writer, and translator should consciously look for ways to make the user’s experience less dissonant. To achieve this, translators should avoid using words or phrases that are too specific to a locale. The choice of vocabulary, including any slang or references to specific places or events, should be as generic as possible within the major language group, so that it will be understood as widely as possible. Words that are unfamiliar or sound “foreign” will likely distract the users from their task and make the application seem less supportive. The language used in the application should convey the appropriate level of authority (for example, policy statements should sound authoritative) and the appropriate tone (for example, helpful hints may be more or less formal in tone depending on the audience expectations). It is worth considering that in many languages, the written language and the spoken language are different—the written language is far more formal. For example, in French the way that ordinary people speak is radically different from the formal written language. Designers need to consider which tone is most appropriate for the content and the audience. As always, it is important to have a native of the region, not just someone who speaks the language, working on the actual translation to influence these decisions. TimeAnother distinct difference between cultural groups is the way that they think about and represent time. In working with computer systems, users frequently deal with time elements—sorting lists in date or time sequence, entering time periods for queries, receiving reminders of due dates, scheduling appointments, making reservations, and so on. It is important to make sure that any time elements are designed to be familiar to the target audience, since they are so often encountered. Diverging from local expectations can create significant attitudinal and performance barriers. For example, we consulted on one project in which users who were responsible for a scheduling task complained about being expected to enter start and end times on a 24-hour clock. Because they were accustomed to a 12-hour clock (clarified with AM and PM), they had to stop with each entry and calculate in their heads the correct time as required by the system. Earlier in this article we touched on the subject of date formats. Interestingly, people who work internationally and have experience with different standards for date displays may need more help in interpreting dates than those who do not. During one international design session, we noticed that Europeans (along with those of us who are “adopted Europeans”) would habitually write out the name of the month for the first 12 days of the month (e.g. “12 Jan 2001”), but would switch to all numbers when writing the remaining dates (e.g. “13/1/2001”). This was a way of avoiding dates that appeared ambiguous (e.g. “12/1/2001”—is that December or January?). Designers should look for ways of removing this ambiguity without increasing the burden on the user. We are skeptical of a recent trend in web sites to use three drop-down selections for each date to be entered, which eliminates the ambiguity but increases the data entry burden. This is acceptable for infrequent use and the entry of one or two dates, but not for regular use. Time periods are also different from one culture to another. Probably the most commonly used time period, the week, is not as straightforward as one might expect. In the US, the calendar week starts on Sunday, whereas in other countries it is common for the week to start on Monday. If the labels on a pop-up calendar are not very clear, a user might easily overlook this difference and make an error. Some applications allow the user to search for transactions entered “last week” or “this month” instead of entering start and end dates in the search criteria. Designers must consider the cultural assumptions inherent in these phrases when preparing for an international audience. A phrase like “the current tax year” would have a different definition in different countries, while a phrase like “the last fortnight” might not translate at all. Colloquial phrasing has been known to produce pitfalls (consider the phrase “half eight,” which means 8:30 in the UK and 7:30 in some other European countries!). Special days and holidays, of course, differ from one country or culture to another. Even with the growing awareness of diversity and multi-cultural staff, we would avoid reference to special days if possible. There are exceptions, such as help content, training materials, or performance support tools which need to provide relevant examples and context-specific information to support the user’s job. For example, a performance support system for a retail application in the US would have to mention the Christmas season and the back-to-school season, since these are a key part of the user’s work context. However, if this performance support system were made available to an international audience, the content would probably have to be completely rewritten. Other exceptions might be calendars, scheduling applications, and collaborative software environments, where informing users of a cultural circumstance such as a holiday can be critical to performance. Cultural ExpectationsPeople in different countries or cultural groups tend to have different expectations of how things work. Their conceptual models are shaped by experience in different environments. Through experience, many behaviors become so skilled that a person no longer pays conscious attention to them (in the field of psychology, such behaviors are said to be automatic). These behaviors are very likely to be culturally bound. If we are good designers, we are already trying to design things that work the way people expect them to, but the possibility of an international audience complicates this task. We believe things that may be considered generic in design are in fact only generic because of the cultural conventions of the designers and current majority of users. When preparing products for international audiences, we need to examine our assumptions. Users may have different expectations about the flow and placement of information on a page. The standard of reading across from left to right is a Western cultural expectation; Arabic cultures read right to left and the Chinese traditionally read from the top right to bottom left. We do not know how the user’s comfort with the software application is affected by a change from the traditional direction of reading and writing. We suspect that even if the user adapts to a seemingly “unnatural” screen display, their culturally traditional reading direction may still impact eye movement. Generally, we consider the top left of a screen to be the “entry” point, with the lower right being the “exit” point – that is why common commands, controls and titles are top left, and often buttons (such as “Next”) are placed toward the bottom right. Thus, cultural background may influence user performance with directional actions and may suggest the optimal placement of controls on a screen. We hope that in the future, the eye tracking research being done in the field of human-computer interaction may be able to clarify this. People in different countries also use equipment that works differently. A prime example of this is the computer keyboard, which has a different layout in different countries. This could potentially affect performance for users working with software that was originally designed for a different keyboard—special characters or control characters may not be there. We have heard from people working abroad that this is especially challenging for touch typists who are forced to move from one keyboard to another. For example, an American who was recently in Eastern Europe told us that she had been surprised to find a keyboard missing the familiar “@” symbol—to type this symbol, she had to learn the key combination “ALT-64.” Some of the differences affect the keyboard shortcuts that designers provide to speed up tasks for expert users. For example, Figure 3 shows the different placement of the CTRL+Z key combination on the German (and various eastern European), French, and US keyboards.

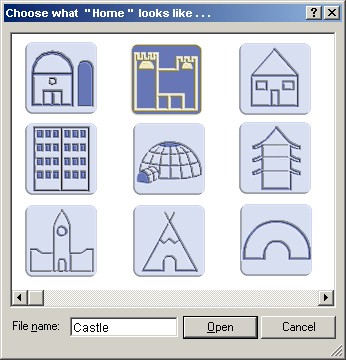

Another performance problem with different keyboards is the potential lack of special characters needed for correct spelling of proper names. For example, we heard from Americans working in Bosnia that the original Bosnian voter registration was done several years ago by international observers who did not correctly enter the special Slavic characters in people’s names. There are two different accented versions of the letter “C” and three versions of the letter “S”, but the internationals simply typed “C” and “S” (probably using American keyboards that did not contain the Slavic characters). This caused significant problems in subsequent elections, when Bosnian voters returned to the polls and were told that they were not registered to vote, because their correct names could not be found in the database. The voters were angered and much time and effort was spent re-entering voter records. There are also more subtle differences in proper names across countries. The sequence of a person’s name—as well as what the “first” and “last” names are called—is a cultural convention. For example, in some eastern European countries and in Asian countries a person’s family name is written before their given name, without any punctuation between (e.g. “Washington George”). An application that did not respect this convention might be harder for users to adapt to because it would require extra mental effort. There may also be other local conventions about the display of names. For example, in France a person’s family name is always printed in all caps (e.g. “George WASHINGTON”). An application that did not respect this convention would still be understandable to the users, but would continue to seem foreign. Representation and implied meaningAnother important difference between cultural groups is their understanding of symbolism, which encompasses visual icons, sounds, colors, and metaphors. Some symbols that we consider generic are actually a matter of cultural convention. For example, we know of a large-scale computer-based training initiative in a multinational corporation where symbolism led to significant performance problems. The training department was surprised to find that while Americans were scoring high on the CBT, most Germans were failing. Upon investigation it was discovered that the CBT required users to click on a checkmark icon for “yes” and an “X” icon for “no.” In Germany, the “X” meant “yes,” so many users were selecting the opposite of their intended answer. Other symbols that represent real-world objects may not be understood across cultures (for example, a literal representation of the US standard manila folder may not be recognized in other countries). With the rapid increase in web use, people are creating their own icons and mixed icon/word controls. This increasing divergence from any de facto “standard” could be a precursor to greater localization of icons.

Auditory interpretation may affect performance when users are working with audio and video materials. The dialects and accents in spoken language are automatically associated with meaning. Consider the difference in effect between a Boston accent and a Georgia accent in the US. The same type of difference exists in other languages. For example, speakers of Parisian French tend to think that Belgian French sounds uncultured and inferior. In some languages the difference is much more extreme. People in the north of China may not even be able to understand the dialect of Chinese spoken in the south of China because the pronunciation and words are so different. Color can convey different meaning in different cultures. It can also be unwittingly loaded with meaning. For example, in Bosnia red is the color of the Serbs and green is the color of the Muslims. Any use of those colors can potentially stir up hostile feelings that an outsider would not have anticipated. However, we believe that color tends to convey meaning in context, so it may be dangerous to generalize too broadly about its use. For example, we were in a developers’ meeting when a requirements analyst cautioned the group that the use of the color red in error messages might not be good for internationalization, since the Chinese associate red with happiness. The two native Chinese developers in the meeting raised their eyebrows in surprise. One of them said, “Now I understand! This must be why the Chinese drive their cars with the tachometer in the red, because they feel so happy… until the engine stops working!” Metaphors that are commonly understood in one culture may not translate well to another, which poses a challenge in design. People who work in the performance support arena will recognize that the “coaching” metaphor has been widely used to suggest a friendly expert guide. This metaphor is frequently reinforced by images or words that tend to center around a specific sport. For example, we have seen numerous “Coach” buttons decorated with baseball cap icons and at least one performance support tool that made extensive use of the football metaphor, including green “grass” with marked field lines. The performer’s localeWe have seen in many applications the assumption that the performer is situated in only one country. However, this is not always the case. There are an increasing number of people who live and work in more than one international location because of business travel and job postings overseas. We believe there is a need to provide the flexibility to support those who do, so that their transitions from one place to another are as seamless as possible. For example, we noticed that a popular consumer web site holds a single profile (multiple addresses, credit cards, etc.) for a person who lives and works in both the US and the UK, but cannot distinguish where to ship from or what to charge based on the shipping address selected. The .com and .co.uk sites are different in all respects except the user’s personal information, but lead the user to believe they are connected. Disconnecting the ProcessWhen preparing a product for an international market, it may not be enough to convert the existing product to a foreign language version. Even if the information is translated sufficiently to make it understandable, the processes themselves may not make sense to the performers or may not adequately support their needs. This is because ordinary tasks, standard practices, and work environments may differ significantly from one country to another. The process becomes “disconnected,” diminishing job performance.

To plan ahead for supporting a process with an international audience, we analyze it by asking questions like these:

There are differences in standard working practices from one country to another that may affect how well a particular software application fits into the local environment. Designers should gather as much information as possible about the tasks and the work context in other countries to identify the types of differences that can be expected. For example, in some European countries it is typical to take a two-hour lunch and extend the working day later into the evening. A staff scheduling software application designed in the US would need to accommodate this practice in order to fit in. The number and types of staff in the work environment may also be different. We heard from a German in a multinational corporation that the company’s internal project staffing processes assumed a much larger and more hierarchical staff than his branch of the company actually had. One person typically took on several roles. There is also the need to comply with different regulations in different countries. For example, we know of a large consulting firm that had difficulty rolling out a training system to its European branches because the system did not capture course completion dates and status in the way that was necessary for ISO9000 compliance. Similarly, any software purchased by the US government is required to comply with Section 508 standards for accessibility to people with disabilities. It is useful to know about these types of standards and practices as early as possible to make sure that the design and the business rules are configurable enough to accommodate them. Because work is done differently in different countries, task analysis becomes very important. The expected sequence of actions, the size and scope of the task, the inputs, and the standards for success may be different. This becomes an important challenge for performance support, where the purpose is to guide the user through the task to achieve a successful outcome. For example, we sometimes introduce a sequence as a way of supporting a novice user. However, if this sequence runs counter to the local organization’s expectations of how the process is normally done, it may instead increase confusion. There may also be an expectation of the degree of control that a user would want to have over the sequence. In some cultures that value individuality, users may want to exert more control over their actions, while in other cultures users may not have this expectation. There is also a need to anticipate which tasks are considered related. For example, in the US we might think of “change my address” and “change my direct deposit” as related tasks, because when people move from one place to another they are also likely to change banks. This is because in the US the banks are statewide, not national. In many other countries where there are national banks, these tasks would not be thought of as related because when people move their bank account stays the same. We recognize that this sounds daunting. It is not practical or desirable to revisit all of the tasks in a software application when preparing for an international market. In order to focus and prioritize this effort, we have started to identify ways of categorizing tasks as “high-context tasks” or “low-context tasks.” In the translation field, others have written about high-context and low-context cultures/languages. A high-context language is one in which there are many references to things that are not spoken directly but are assumed to be understood by all speakers (Hall, as described by Hoft, 1995). Similarly, we have defined “high-context tasks” as those that are more culturally bound. When we review an application, we look for high-context tasks that will need more attention to localization, low-context tasks that can be internationalized, and rules that should be made locally configurable. For example, in a training management application, the task of registering for a training course is low-context, and we would focus on making it generic enough to be understood internationally. The task of creating development plans and mapping learning to specific job requirements, on the other hand, is high-context, because it is tied to cultural expectations about career advancement, employment duration, incentives, and continuing education, as well as local policy. A third task, getting manager approval for a course, is medium-context, because although it is related to cultural expectations, it is more closely tied to internal organizational rules, and must be configurable. Although supporting the work process in another country is a primary goal, we must not forget that in some situations it is necessary to accommodate multiple countries or cultural groups at once. For example, it is not enough to support the local currency if people need to use multiple currencies as part of their standard work. A few years ago, a review of small business accounting packages showed they could be configured to accept input in one of several international currencies. However, once the user had gone through the setup process and selected a currency, that currency remained the default, and there was no ability to enter amounts in other currencies. This was a problem for international businesses, because the users were forced to manually convert the currency amounts. Similarly, in collaborative work environments it is important to support multiple language groups, because project teams and design groups are increasingly made up of international participants working in different places, different time zones, and different languages. Disconnecting the InformationPreparing information for an international market is not limited to the language translation. It also includes making sure that the content is relevant and understandable. In terms of the three-element model of performance, even if the process is understandable to the performer, the information content may not make sense. In this case the information becomes “disconnected,” diminishing job performance.

To prepare information for an international audience, we analyze it by asking questions like these:

The basic issue is being able to read the information. Imagine a situation where you have just gotten off an airplane in Kuala Lumpur or Delhi. The process of finding your way around an airport is familiar to you as an experienced traveler, but there is no easy way to puzzle out the written language. The “data” on the signs has no informational value to you. This is exactly the situation that prompted the development of international symbols for the physical world. These symbols have become at least recognizable enough to provide the informational value you need in that context. There is not yet an equivalent symbolic “language” for software. To some extent this is what icons attempt to do, and some succeed by default if not by design, because certain software is now widely used around the world. Users in different cultures may have different approaches to finding information. On the web, seeking strategies are increasingly relying on search. Search is not the most effective method, but other strategies are affected by the way that people think about and categorize content, which varies from country to country. For example, the Library of Congress cataloguing system is applicable only in the US; other countries may have their own standards or no standard. Users’ expectations of the layout and organization of information may also be different. For example, in France, reference books have the table of contents in the back rather than in the front. We have heard that it takes many months of frustration before an American student acquires the habit of taking a book off the shelf and immediately flipping to the back to see what it contains. If users of our software have similar expectations that we violate unknowingly, their performance will be diminished. Although the organization of content depends primarily on the type of content and the situation in which it will be used, culture may also have an effect. For example, in Japan it would not be unusual for a user to take the manual home and read it before working with an application for the first time, while in the US people prefer to scan a quick-reference card and figure it out as they go, using task-specific help if they get stuck. It is important to review warning messages and feedback for cultural relevance. The instructions that accompany a warning and specify “appropriate” action may need to be revised for different audiences. The required action (e.g. contact the help desk, or policy-specific information) may be referring to an infrastructure that is not there in a smaller country. Thus, warning messages cannot afford to be too rigid. This may be the case even when common international practices are the goal, such as when carrying out multinational drug trial research. The standardized software tools must still communicate effectively to local users. When reviewing content, it is important to notice any local references and examples that rely on cultural context and may not translate. We know how valuable it is to provide examples in performance support, but we must be aware that an example that makes sense in one country may just confuse users in another. For example, an application used in the insurance industry would need examples based on state regulations. However, if an insurance company were multinational, it would need completely different examples to reflect the different types of regulations that exist in countries with a single national regulation. As designers, we need to build this flexibility into the information architecture so that it is easy to pull out an example and replace it with something different that is more appropriate to the culture. In the past, many software companies have treated localized versions of the information as a secondary concern. Localized documentation and user interfaces are often released months after the initial language version, which has an effect on product distribution and support. For example, we recently saw a product that was available on the Internet for downloading, but only in English. There was a notice asking people to check back in a few months for the western European language versions. We suspect that many potential customers would forget to come back and look again. If they decide to download the English version, they may not be able to get support from local staff. For example, we heard of a situation in which European users in a multinational corporation received a new version of a software package and began calling their local help desk with questions—only to find that the help desk staff had not yet received instructions on the product in their language. It creates a huge hit to productivity and credibility when the support staff cannot meet their end users’ needs because they do not have adequate tools available in a language they can understand. ConclusionsOver many years of experience in the software development field, we have seen how easy it is to reflect personal bias and local assumptions into the way that software works. Breaking those habits is certainly a challenge, but one that increasingly must be met. While we, like most designers, may have more questions than answers, there are a few things we can conclude from our explorations into internationalization. In fact, most of these principles are also general principles of good design—when they are done well, we have found that they contribute greatly to the internationalization effort.

ReferencesCross, J. (1999). Internationalize with Localization. Microsoft. Online, Internet. February 1999. msdn.microsoft.com/library/periodic/period99/vjp9922.htm Dickelman, Gary. (1996). Gershom’s Law: Principles for the Design of Performance Support Systems Intended for Use by Human Beings. CBT Solutions, September/October 1996. As read Online, Internet. www.pcd-innovations.com/ del Galdo, E.M. and Nielsen, J. (eds). (1996). International User Interfaces. New York, N.Y.: John Wiley & Sons. Ebben, S. & Marshall, G. (1999). The Localization Process: Globalizing Your Code and Localizing Your Site. Microsoft. Online, Internet. 21 April 1999. www.microsoft.com/TechNet/Analpln/glolocal.asp. Hall, Edward T., in Hoft, Nancy L. (1995). International Technical Communication: How to Export Information about High Technology. New York, N.Y.: John Wiley & Sons. Ishida, Richard. (1997). Challenges in Designing International User Information. Online, Internet. Posted 28 October 1998. www.xerox-emea.com/globaldesign/paper1.htm. Norman, Donald A. (1998). The Invisible Computer. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Sun Microsystems, Inc. (2000). I18N Verification Checklist. Online, Internet. www.sun.com:80/developers/gadc/i18ntesting/checklists/index.html. W3C (World Wide Web Consortium). (1998). 18n/l10n: LISA – Internationalization/Localization. Online, Internet. 3 July 1998. www.w3.org/international/o-lisa.html.

The content of this article may be referenced with the appropriate citation information included (see below). The entirety of the article must not be reproduced without written communication with ISPI (www.ispi.org). Also, we would appreciate your notifying us if you intend to use these concepts or images, as we are curious to know where they prove valuable. To cite the material, please include the following information. We recommend the format: Battle, Lisa and Degler, Duane (2001). Around

the Interface in 80 Clicks. Performance

Improvement (EPSS Special Edition). ISPI, 40(7), August 2001. As viewed online,

www.ipgems.com/writing/80clicks.htm.

|

|

© Duane Degler 2001-2008