|

||||||||||||||||

Knowledge Maintenance Strategies: Gaining User Involvementby Duane Degler What follows is a summary of ideas and approaches presented at Knowledge Management 2001, London, England, 3rd April 2001. IntroductionOver the recent years, Knowledge Management has been gaining significant momentum within organisations. Much of the emphasis, particularly on the part of the suppliers who are wrestling with the evolving technology, has been on the acquisition and storage of information, and how it can be retrieved more flexibly. But think about this: if I see an article or item of information that I think is interesting, I am likely to copy it for other people. A physical article might trigger my making and circulating 10 copies, of which three get read, three get thrown out, and four get put in a pile “to look at later.” Valuable, yes. Insightful, yes. Available? No. Taking up storage space and making other things harder to find? Definitely! E-mail is even worse—it is so easy to forward items to people in my address book, that hundreds of copies of the information can proliferate. I looked this morning—over 600 items in my inbox, and that’s with a recent cleaning. If I spend only 6 seconds evaluating each one to keep or delete, that is still one hour of my time that I am unlikely to spend cleaning my inbox. And it still is not effective shared information. If someone else wants the information that I hold there, I can search for it, but everyone’s time is affected. It is easier and faster to have a conversation and rely on my memory of the information, than to have both the information and the conversation—the combination of the two being a richer sharing of knowledge. I have seen shared network drives filled with documents and presentations, many gigabytes worth, stretching back over many years. It is easier today to store and access that material. It needs to become easier to review or remove that material when it is no longer appropriate to the organisational mission. How can organisations work to ensure that shared knowledge remains relevant over time? One key way is to involve the person using the information. In this paper I explore:

What Knowledge Needs to be Maintained?For the purposes of exploring the subject of maintenance, I will focus on explicit, formal knowledge that is able to be accessed by more than one person, and thus has value to an organisation generally rather than just a single individual. The maintenance of dialog and conversational threads, though very important as a part of knowledge sharing, is a more complex subject for another day. Knowledge is often only apparent through the actions of individuals, and the outcomes they achieve—you demonstrate that you “know” something by the actions that you take. Shared knowledge is communicating something that helped one person achieve a quality outcome, so other people can achieve the same—or better—outcome. Maintenance, in this context, is making sure that the information that is shared and used continues to encourage successful outcomes. To promote user involvement in maintenance, there has to be a shared belief in the value of the knowledge, and thus the value of keeping it relevant and accurate. If it isn’t seen to be valuable, people won’t waste their time on it. Active User Involvement in MaintenanceUsers should actively get involved in:

1. Information UsabilityIn the same way that software is tested for usability, so should the approach to handling information be tested. Comparing information usability with traditional usability testing for software applications and interfaces shows a number of similarities and differences:

Along with the above activities to support the design of the information and the knowledge-sharing applications, it is also important to assign responsibilities for information/knowledge ownership for both creation and maintenance—this may require very different skills and temperaments, and so may not be assigned to the same person. Work to refine the quantity and quality of metadata captured. This is a critical task—if it isn’t done correctly, it will create a huge maintenance burden. The “information about information” has to support the maintenance task. For example, metadata should include anticipated life of an information element, review dates, the authors, owner, further subject experts, and any relevant date where the information was revised or feedback received. Metadata should also carry things that can hook it into applications that provide relevant information embedded in the screen. 2. Capturing FeedbackThe simplest and most common way of asking the users to participate in the maintenance of knowledge is to put simple feedback mechanisms on the page where information is displayed. There are a number of ways this can appear—general guidelines include:

Make sure that the mechanisms for capturing feedback at the point of use do not conflict with the task or the environment. For example, I had a conversation with one help desk application developer whose product included a “rating” section on each page of information. As much as I applaud the recognition that this feedback could help the quality of the knowledge base, the idea ran aground on two points:

The answer may lie in a more holistic approach:

Decide how much feedback you need. If you don’t intend to use it, don’t capture it! Users who are motivated to provide information are easily de-motivated if they feel they are being ignored or the contribution is not valued. The best ways to make sure people feel their contribution is valued are:

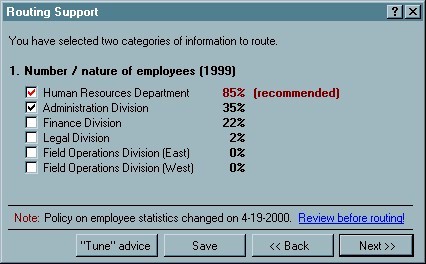

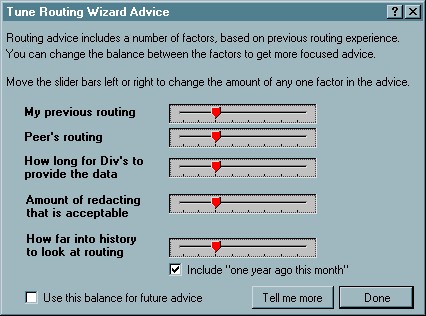

Incentivizing people to involve themselves in “knowledge quality” is a good thing. Incentives are those things that motivate people to become involved and commit their attention to something. This doesn’t necessarily mean bottles of champagne or big bonuses—research has shown that this is not always as effective as people think. The biggest incentive for involvement in knowledge maintenance is often the improvement in the available, useful knowledge itself. Stealth Knowledge Management – Learning from UseA useful concept I and some colleagues began developing a few years ago is “Stealth Knowledge Management.” When computers are used to carry out job tasks and make decisions, there is a growing record of the way decisions are made – embodied in the way the applications are used. The rules of decision-making are not artificially defined in advance, but based on actual performance—whether that performance is carrying out a task or seeking knowledge from a knowledge base. The rules are as dynamic as the experienced people who perform the tasks day-in and day-out. The capturing of this experience (“knowledge from actions”) can be valuable to less experienced people performing the same tasks, and can also help content owners understand the value of the information in their care. The key factors of Stealth Knowledge Management are:

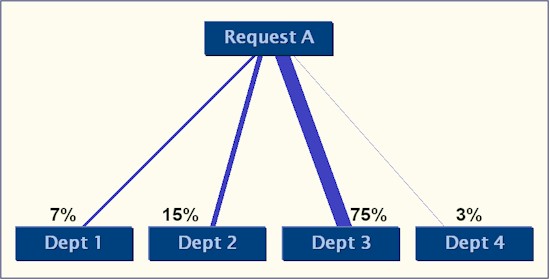

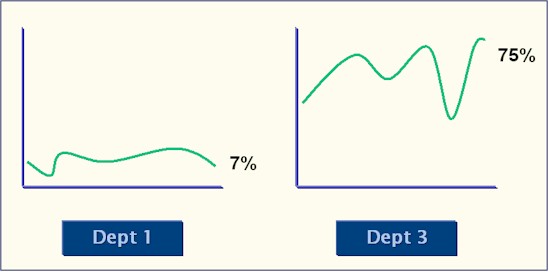

For example, for one client the challenge was to receive requests for information from the public, and route these requests to the most suitable departments for providing the reply. The knowledge of how to interpret a request and identify the department(s) most likely to hold relevant information was rooted in the experience of one person who had been doing it for over ten years. When that person was away, routing virtually stopped. This is a classic problem in knowledge management, that could not be solved by informing or training a second person—the job circumstances were too dynamic. However, by tracking the nature of the decisions made when categorizing and routing, a dynamic picture of those decisions could be created. The rules could change as the types of information being requested by the public changed. The routing challenge and part of the solution are illustrated below.

Using stealth knowledge management, the hidden business rules (tacit knowledge) become overt (explicit knowledge), while not becoming so rigid that they lose their meaning. The user remains in control of the use of knowledge, and becomes an active contributor without being distracted from the task or having to make an extra effort to participate. Stealth knowledge management contributes to an ecological model for maintenance, where information is self-sustaining and begins to have a life of its own. The model is appearing primarily within communities of practice and online group interaction, where there are no formal rules for knowledge management, but the group’s contribution to the knowledge base and use of the information identifies the value—and again, this is done dynamically. This also allows the group or the information to die naturally when it no longer has value. ConclusionsAs mentioned above, active maintenance that involves users in the process requires the combination of:

Without both of those elements, the burden for maintenance is probably going to fall back to a select few, whose job will be much harder. When users become actively involved, you begin to learn the real value that knowledge has to the people who use it.

The content of this article may be referenced with the appropriate citation information included (see below). I would appreciate your notifying me if you intend to use these concepts or images, as I am curious to know where they prove valuable. The entirety of the article must not be reproduced without written communication with Duane Degler at IPGems. To cite the material, please include the following information. I recommend the format: Degler, Duane (2001). Knowledge

Maintenance Strategies: Gaining User Involvement. Knowledge Management 2001, London, England. Online: www.ipgems.com/present/knowmaint.htm.

|

|

© Duane Degler 2001-2008